Lewisham & Greenwich NHS Trust’s maternity service has found a unique way to fill vacant slots on the roster – by carving shifts up into smaller slices and offering choice.

Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust are an accredited Timewise Trust – an accolade that is awarded to Trusts that demonstrate commitment to enabling flexible working for their teams Part of this is developing creative and innovative approaches to working patterns and arrangements.

Any Hours is an example of such innovation. The immediate post-pandemic period inspired ‘Any Hours’, the brainchild of Susanne Chatterley, Associate Director of Midwifery & Neonatal services at Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust. More than 300 midwives work across the Trust, delivering 5,000 – 7,000 babies a year.

A standard shift in midwifery is 12.5 hours and is set at 8.00am – 8.30pm, or 8.00pm – 8.30am.

A full time job requires working 13 shifts across a month – 3 weeks of 3 x shifts and 1 week of 4 x shifts. There are typically unfilled shifts within any NHS roster. The Nuffield Trust estimates that there around and around 8,000 to 12,000 unfilled nursing vacancies on a given day in England. In many cases, existing staff try to take on extra shifts where they can, or else agency staff are used. Traditionally in the NHS taking on an extra shift requires commitment to the full 12.5 hour day.

Susanne realised she could boost capacity by challenging the ’12.5hrs only’ mindset, when it came to filling vacant shifts.

She says: “In 2022, we had just gone through the second significant bout of Covid. I recognised that we had one group of experienced midwives who routinely picked up one or two extra 12.5 hour shifts a week – and these were the staff who were burning out. There was also a second group, with just as much experience, but who simply couldn’t pick up such lengthy additional shifts. They wanted to help their colleagues – but had young children to pick up from school, or elderly relatives to look after in their day. I thought to myself – how do I unlock this group, and how can I help the staff experiencing burnout? Then I thought – what if staff could choose their extra hours? What if they could stipulate how much extra time they could give – 3, 4, 8 hours, whatever it is – and choose when to work them?”

Susanne had a conversation with the midwifery team and followed with a survey to see if they’d like to work extra paid shifts and what hours they would pick if it was up to them. The results came back showing a strong desire to work more, especially against the background of the cost of living crisis, but that for many midwives, an extra 12.5 hour shift was too long. Susanne says: “All I had to do, was make it work.”

That was two years ago. The scheme has been an outstanding success. Wherever there are shifts that are unfilled, Any Hours allows midwives to choose the number of additional hours they want to work, and when they would like to work them. Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust data shows that since the Any Hours Scheme was enacted, it has it has enabled, on average, 300 hours of shifts to be filled each month, equalling two whole time equivalent midwives. This has reduced reliance on agency staff, and increased satisfaction with the team.

This has been achieved without buying in any additional software or making significant changes to the online rostering system staff already use to book shifts via their phones.

Susanne says: “The key difference is that all unfilled shifts are open to ‘Any hours’ – I let them ask for any additional hours they want, whatever the length and whenever they are. We always end up with a much fuller roster than we have had in previous years.”

“I also have a rule which is ‘hard stop’. We let staff finish their shift exactly when expected. If we start keeping people beyond the agreed shifts then the whole system starts to fall apart. It works because people feel they have autonomy, control and balance.”

“We also worked hard on making sure the extra shifts would work. Patient safety is of course our paramount concern. We spent time with senior clinical colleagues to think about how a 3, 4, or 5 hour extra shift would work. In terms of patient care, we wanted to ensure women have the same person with them as much as possible through their journey.”

“When you start thinking about shorter chunks of time, say a 3 or 4 hour shift rather than a 12.5 hour one, you need to think through – what can you usefully do in that period? It isn’t enough time to start a birthing journey with a patient. But you can support the whole ward and the midwives who are doing that. You can do baby checks so others can go home sooner, you can do the drug rounds, you could maybe host 1 clinic, or do postnatal visits. The key was finding jobs that fit the shorter hours.”

“And what I found was – people got really creative! One midwife comes at 11pm and she stays until 5 or 6am. I would never ask anyone to do that kind of shift routinely, but for her, it means she can work while her own children sleep and she is back for the school run. It fits her life.”

“We really saw the benefits over the Christmas period. Staffing is always a headache at that time of year, you usually end up redoing the rota 2 or 3 times and invariably end up short of staff.”

“But last year, I crunched the numbers after Christmas and realised we had equal to 4 whole-time equivalents more than usual– the best fill rate we have ever had. All those shifts would have otherwise been unfilled. People came in, working in 3 or 4 hour bursts to help out, and for the extra money at an expensive time of year. I felt all warm and fluffy on the inside when I saw that! I spoke to colleagues – they said they would never have come in to work a full extra shift because it would have interfered with their plans. What’s brilliant is – we are retaining staff known to us, with experience and skill who knows the service inside out, rather than having to just use agency staff.”

“The scheme has been going for two years now, and is well established. I don’t think I have ever turned anyone down – we are always able to offer what people want. The key has been flexibility and handing over a sense of control. People now have their regular patterns they have fallen into. Patterns that suit their lives.”

“What’s exciting is that Any Hours is completely replicable across the board. It works within the existing system. It can work in other departments, and for other Trusts.”

Any Hours is a part of Susanne’s doctorate, focusing on midwives who take up and use the offer, and colleagues who work with them. Susanne is completing a DBA in Business Administration at Aston University; Business School in Birmingham.

Susanne is already working on her next innovation project: ‘Any Speciality’, aiming to retain midwives who are 5 years + qualified (though those who are less qualified can also take part).

Any Speciality is a programme that encourages all midwives to spend 15 hours a month, or two days, in a different speciality of their choice. This allows colleagues to improve the competencies and skills needed to help their career progression, or even to directly apply for a specialist midwife role at the trust. To date, speciality teams have recruited nine midwives following Any Speciality contact at Lewisham and Greenwich NHS Trust.

Susanne says: “The opportunity is to ‘try before you buy’, when looking at another speciality as a possibility. I took one of the many of vacancies I had and chopped it up into 10 pieces, which leaves you with 15 hours a month (one tenth of a full time job). We offer this to anyone who has an interest in another speciality. The jump between core to speciality midwife is really big nowadays. And often, when someone makes the jump they don’t realise what they are signing up to – and they drop out or move on quickly if the role is not what they expected it to be.”

“Any Speciality is available for 1 year after that time – you may realise you hate it! That’s ok – you have tried it. You aren’t locked in. Or you just might love it. When the right job comes up, you can apply for it as you have the lived experience.”

Published July 2024

UCLH is a large teaching hospital, part of the Shelford Group, which has over 10,000 staff working across 10 London sites. The leadership team is keen to create a work environment in which staff feel valued, encouraged and supported, and as part of this, has sought to explore how to improve work-life balance.

Like many organisations, UCLH implemented remote and hybrid working for office-based staff during and after the pandemic. However, there are unique operational constraints in some patient-facing and clinical areas, mainly wards and teams delivering 24-hour services. Hybrid working was not a viable flexible working option for ward staff and the leadership team felt it was important to find other ways to offer flexibility for these teams. This was reinforced by a survey in 2021, which revealed that 51% of staff felt they had a good balance between work and home life, and just 48% felt that UCLH was committed to helping them balance these two elements.

Following this feedback, UCLH launched a new flexible working policy in 2022, which offered a more proactive approach to flexible working. This included the implementation of a new electronic rostering system, which in turn opened up opportunities to explore innovative approaches for ward-based staff.

However, the team felt they needed to bolster local resources with dedicated external expertise to drive the project forward, including the support of someone with experience in delivery. A member of UCLH worked with Timewise on a previous project at another NHS Trust and approached us to provide support for the self-rostering project.

Our team worked with UCLH to pilot a self-rostering approach, which allows staff to select their preferred shift arrangements and days off. These requests build a draft roster, which is then reviewed and adjusted (if necessary) by the ward manager / senior nurse. On completion the roster is 1st level approved by the ward manager followed by a 2nd level approval by the matron. It gives staff more input and control into the shifts they work, and makes the rostering process easier, and quicker, for the ward managers.

We agreed to pilot this approach with four wards of varying sizes, which were spread across two sites, and represented different clinical divisions and ward size. Approximately 152 staff were involved.

Working closely with the UCLH team, an integrated project team was created. We began with a research phase that looked at existing workforce data, and explored how the staff on the four wards were currently using the system. We then brought representatives from each ward together to work with us to design the pilot, setting out the principles and etiquette that would allow self-rostering to run smoothly.

We also sought to engage directly with the ward managers and matrons from each ward, knowing that they would be responsible for managing the new roster on a day-to-day basis, and for fielding questions about how to use it. And we created a range of resources for the UCLH intranet, which set out the parameters of the project, explained how to use the roster and answered common questions.

Having sought to get everyone on board, we then ran the pilot across the four wards for three months. Feedback was gathered through ward visits and surveys, and fed into a formal evaluation of the pilot, which could be used to steer a potential wider rollout.

We identified potential challenges before we began the pilot, such as the technology limitations, and the ‘first-come-first-served’ nature of the system being potentially contentious. However, the roster team provided the necessary training to ensure the rostering technology could be used effectively. The project team presented and communicated clearly the ‘etiquette’ involved in this new approach to rostering – encouraging staff to consider the impact of the shifts they were selecting on the wider team, by drawing on the Trust values. This helped mitigate these potential problems, none of which turned out to be issues during the pilot itself.

We did encounter some implementation challenges as the pilot developed. For example, although self-rostering should be used to book shifts or days off, some staff began using their allocations as a way to book time off work, instead of going through the annual leave process. Similarly, while each shift needed a senior nurse to select the nurse in charge shift some staff were not booking into these shifts. This impacted the overall shape of the roster and so the issues were addressed, and both of these were quickly overcome through conversations at a local level.

In terms of outcomes, we sought to evaluate how many staff were using the new roster approach to input their preferred shifts, and how many were approved. By the end of the pilot:

Critically, this new way of rostering was used by all staff groups, though slightly less by the unregistered staff. Positively, the ward managers reported they saved time, due to a large proportion of the roster already being populated before they got involved and had fewer swap shift requests after roster publication.

The UCLH team provided a detailed evaluation of the pilot, and approval was obtained to rollout self rostering across the nursing teams within the Trust.

Following the successful pilot, self rostering has been rolled out to the nursing teams in a further 43 wards across two hospital sites. The only exceptions are the emergency and critical care units (three wards) who had recently established their own specialist rostering arrangements including rolling rosters.

In order to enable roll out at this scale, the 43 wards were grouped into six cohorts, who went live with self rostering in a phased pattern across a period of six months. Timewise supported the UCLH project team and steering group to agree the roll out approach, standardise roster rules and get the engagement, training and comms right, building on our learning from the pilot. A valuable addition for the roll out was the appointment of a ward advocate for each ward, whose role was to support the project team and the ward managers by liaising with nursing colleagues, ensuring people understood the new approach, and flagging any issues or concerns early so that the roll out could progress smoothly. The steering group met monthly to monitor progress, measuring take-up and approval rates and ensuring they were in line with the high levels achieved in the pilot.

The nursing roll out is now complete, and some non-nursing teams across the Trust are starting to express interest in this way of working and exploring the benefits it could have for them also – watch this space!

Claire Stranack, HR Business Partner at UCLH, has this advice for anyone considering a similar project:

Inge Cordner, Lead Nurse for Nursing & Midwifery Workforce, has some additional suggestions from the frontline:

Timewise brought a huge amount of experience and resources and supported us at every stage of the process. They acted as a critical friend, supporting and facilitating design and engagement sessions, and driving the project forward at a pace we could not have achieved alone. There is no way we could have delivered this pilot within this timescale without Timewise’s involvement.

Claire Stranack, Human Resources Business Partner at UCLH

Often working in the NHS we have so many competing priorities that you can often be pulled in many directions. Someone outside of that space, supporting with external expertise, as provided by Timewise, meant we were able to hit the ground running whilst being able to build our own organisational knowledge at the same time. The project was well managed and enabled us to use our time efficiently. Thank you, Amy!

Inge Cordner, Lead Nurse for Nursing & Midwifery Workforce, UCLH

Published June 2024, updated May 2025

By Amy Butterworth, Consultancy Director

As Marcus Buckingham notably said, “People leave managers, not companies.” That’s why companies that take retention seriously tend to make sure their managers have the skills they need to lead and support their teams. But it’s fair to say that recent events have created some fundamental new challenges for managers to deal with – and in many cases, the training hasn’t caught up.

Despite the move to remote working during lockdown, and the subsequent shift towards a hybrid model, research from the University of Birmingham found that only 43% of managers had received any training in how to manage hybrid teams. It’s not a stretch to say that this could be why 47% of line managers are finding work more stressful than pre-pandemic. And with many companies now struggling to find the right balance between time spent in and outside the office, having skilled-up line managers is becoming even more critical.

It’s for this reason that we joined forces with our friends at the Chartered Management Institute (CMI) to run a three-month project, Making hybrid work for you and your team, exploring what’s happening on the ground with hybrid working, and what difference intensive management training can make. And the results surprised even us.

As of 6th April, employers will be legally required to consider requests to work flexibly from day one of employment – effectively extending current flexible working rights from existing to new staff.

The new legislation is just one of a series of measures on the horizon seeking to improve the control workers have over the hours they work. Later this year people working irregular hours will gain a new right to request predictable working patterns. And if Labour wins the next election, the party have pledged to convert these ‘rights to request’ into default rights for all workers and end the use of zero-hours contracts, among other measures.

If successful, these measures could help reduce the well-documented gap between the high number of people seeking to work flexibly, and the limited number of high quality, part-time and flexible jobs in the economy. They could help achieve wider goals such as boosting employment rates, and helping parents, older people and those with health conditions and disabilities to participate in work.

In advance of the new legislation ‘Day One Flex’ legislation coming into effect soon, Timewise is conducting interviews with employers in construction, transport and logistics, retail and health and social care. Our findings so far suggest that, without further action, this legislation will make little difference to staff in the frontline sectors and roles where most low-to-middle income earners work.

Each of these sectors faces genuine complexities when it comes to scheduling – from the need to provide the right capacity and skills to ensure safety on hospital wards and construction sites, to the operational challenges associated with responding to fluctuations in demand in retail, transport and social care. But there are also entrenched cultural patterns that have prioritised employers’ needs for flexibility over those of staff. Cost control measures in these sectors focus primarily on controlling staff costs, rather than the operational efficiencies and improvements that can come from a motivated, well-trained and engaged workforce.

Without this, few of those we are interviewing think the new right to request flexible working would have a significant impact on employers not already engaged in these issues. Interviewees cite the relatively low numbers of formal requests they currently receive, and the ability to reject requests on a broad range of business needs, whether for new or existing staff.

Employers highlight the wider structural constraints they have little control over. In construction, for example, cost and staff assumptions are usually set by developers in the tender phase. These organisations are several steps removed from the sub-contractors that have to deliver site-based works with the minimum number of staff and little room for the inevitable delays.

Similarly, acute budget constraints and staff shortages in the NHS and social care mean there is little ‘slack’ in the system, making it harder for managers to enable staff to request or change their working patterns.

In all these sectors there are employers that are bucking the trend, often driven by difficulties recruiting or retaining good staff, as well as a real commitment to staff wellbeing. Some retailers we are speaking to are choosing to offer regular, stable shifts, provided well in advance. One construction company has created two teams on each project to enable compressed hours and the option to start or finish early, while still providing the supervision and skills required to operate safely and tackle any problems.

The most transformative approaches are seeking to organise work and schedules in ways that enable ‘Shift-Life Balance’, providing greater input, advance notice and stability for all staff and teams. This is in contrast to case-by-case approaches to flexible working arrangements, which employers feel could lead to unfairness and inconsistency, and limit the overall scope for shift-life balance. This view is supported by pilots Timewise has conducted with employers in nursing, construction and social care to test team-based rostering, where staff collectively set schedules through a participatory forum. Employers saw significant improvements in staff engagement, recruitment and retention as a result.

The research is suggesting that this will require sector-wide interventions to ensure all parts of the system coordinate to enable more flexible working. And it needs training and support to build the capacity and knowledge for change among employers, particularly smaller employers. If we can achieve this, it could not only help tackle some of our biggest national social and economic challenges, but also significantly improve quality of life for millions of workers.

Published March 2024

By Claire Campbell, CEO, Timewise

Is the remote vs in-office debate still the only flex topic in town? And if that’s all anyone is focusing on, what are we missing?

There’s a new story every week about companies stopping employees from working some or any of the week from home, with Loreal and O’Rourke just two very recent examples. And yes, we agree that creating opportunities for teams to come together is hugely valuable (as long as it is planned and implemented carefully, so people aren’t just commuting in to sit on Teams calls all day).

But this unrelenting focus on getting everyone in full-time holds two potential dangers for employers. At a general level, it creates a perception that remote is the only flex worth talking about, when there are other ways to provide a better work-life balance. And, more specifically, it ignores the role that flexible working can play in tackling workplace priorities such as diversity and inclusion.

We’ve always believed that the power of flexible working to boost D & I is one of its biggest strengths, and have worked with many employers to build this into their strategies. It’s not rocket science, after all; offering a range of working patterns that take into account people’s different needs is bound to help you attract and retain different groups of people.

Numerous studies bear this out. When Zurich identified a lack of applications from women for senior roles, they launched a flexible working initiative which led to a 66% boost in applications, with one in four of the new female hires choosing to work part-time. And just this month, Wharton reported that when STEM job listings shifted to remote during the pandemic, they drew a 15% increase in female applicants, and a 33% increase in underrepresented minority applicants.

Unsurprisingly, flexible working is also important to people with additional responsibilities or needs. In a study by University of Lancaster, which focused on how remote working can support employees with a disability or long-term health condition, 70% of disabled workers said that if they were not allowed to work remotely it would negatively impact their health. ONS data has shown that, among older workers who have left the workforce since the pandemic and would consider returning, a third said that flexible working was the most important factor (higher than good pay). And a survey of mothers last year suggested that, while 98% of women want to return to work after maternity leave, only 13% think it is viable on a full-time basis.

Clearly, then, the data indicates that flexible working is a good way to attract and retain a wider range of people, including women, carers and people with health issues. So there’s a strong social argument for actively using flex to help these groups enter or re-enter the workforce.

Similarly, it’s worth noting the particular role that flexible working can play in tackling the ‘S’ in ‘ESG’. We’ve written before about the risk of two-tier workforces, in which flexible working is more readily available to people in office jobs than it is to those working in frontline roles (which are frequently lower paid). As this makes it even harder for those at the lower end of the pay scale to access work that fits with their lives, it’s likely to keep people out of the workforce, and so amplify existing inequalities. Better flexible working for all can help close this gap.

It’s equally important to remember that having a more diverse workforce has been shown to make economic sense. 2017 research by McKinsey calculated that improving diversity could add £150 billion a year to the UK economy by 2025, and companies with diverse boards have been shown to outperform their rivals. So there are sound business reasons, as well as social ones, for boosting diversity and inclusion through flexible working.

And on the subject of the business case, our Fair Flexible Futures projects showed that investing in flexible working can pay for itself within three years, due to reduced sickness absence and increased staff retention.

So, instead of going hell for leather trying to get everyone back into the office, it would be better for leaders to step back a bit. To think about whether their business and talent imperatives could be well-served by introducing flexible working – of varying kinds, to match the needs of their current and future workforce – and to invest a bit of time and resources in doing it well.

The arrival of ‘Day One Flex’ rights in April means that now is the perfect time to revisit your flexible working strategy, and embedding D & I into it makes a lot of sense. If you’re not sure where to start, or how best to take it further, we’re here to help.

Published February 2024

By Emma Stewart, Co-Founder, Timewise

Is it a given that working in a creative industry means working all hours? It doesn’t seem right, but it’s certainly the reality of life on set for film and TV crews, where 10+ hour days are not just the norm, they’re hard-wired into production schedules.

And while this has long been the case, things have got worse in recent years. The pandemic and its fallout put significant pressure on people in the industry – 86% of whom experience mental ill-health – and made it harder than ever to hang on to experienced crew. More recently, strikes have caused work to dry up again – and as things are starting to go back to normal, long hours are too. All of which is creating a growing perception that the status quo isn’t sustainable.

I can speak from experience, as one of the thousands of people who left a career in film and TV due to the impossibility of combining the job I loved with the needs of my young family. So I leapt at the chance to explore the options for introducing shorter working days for film and TV crews; to quote Jaws: The Revenge, “This time, it’s personal.” And our findings are now available in our new report.

We began our work in this field in 2022, with an action research project that explored potential opportunities to improve flexible working within the industry. The project was carried out in partnership with BECTU Vision and Screen Scotland, and it indicated that the main challenge was the length of the working day.

So in April 2023 we embarked upon a second phase, supported by BBC Drama Commissioning and The Film and TV Charity as well as our original partners, which set out to see whether productions based on shorter days could be commercially and logistically viable. The question we set ourselves was, Is it possible to go from a 10-hour working day to an eight-hour one, without a detrimental effect on budgets and schedules? (Spoiler alert – yes, it is.)

Michelmores, an all-services law firm with 450 staff and offices in Exeter, Bristol, London and Cheltenham offers agile working (a combination of working in office and at home) to all staff, where possible in the role. Prior to the pandemic, Michelmores had many individual flexible arrangements and sought to accommodate staff requests when possible.

During the pandemic, during which almost all of Michelmores’ staff worked from home, HR and the senior partners foresaw that they would need to re-imagine the workplace once the return-to-office started. It was difficult to know what the range of options should be and to anticipate their implications. They wanted support in developing new ways of working and to engage staff in the process.

Michelmores came to Timewise looking for an expert view, the wider context of what was happening in the greater labour market and thoughts on how to plan ahead. Colette Stevens, HR Director at Michelmores, says: “Timewise have a real depth of understanding of all the different flexible working options, what the implications would be of pursuing them and a strong commitment to understanding Michelmores’ needs, context and ambitions. Timewise gave us a framework and process within which to explore ideas, challenge thinking and think about different options.”

Timewise convened a working group, made up of Michelmores’ Managing Partner Tim Richards, HR Director Colette Stevens and other senior partners. This team developed the firm’s Agile Working framework with Timewise’s input and guidance. Fairness sits as a core principle within this framework: the goal is to provide all employees with the opportunity to balance working from home and in the office, as agreed within their teams. The framework provides a practical structure, as to the ‘how’. By way of guiding values, the group wanted to ensure that:

Team leaders were tasked with helping to identify any underlying issues and collaboratively working through the implications of agile working in detail with their teams. The agreed framework was rolled out for a year-long trial, with regular feedback from staff at all levels.

Recognising the critical role of managers, Timewise ran bespoke training sessions to help them feel capable and confident in implementing the agile working framework for their teams. Timewise then worked closely with the project team to facilitate follow up review sessions a few months into the trial, for managers to share good practice, seek support and ask questions.

The agile working approach adopted by Michelmores has been a great success, with over 80% of staff expressing satisfaction with how they can work, giving them greater choice and freedom. Set this against the wider context of the pandemic’s impact upon the legal profession. A 2021 study by Gartner of 202 corporate lawyers found 68% were ready to start looking for a new job.

Michelmores prides itself upon enhanced talent attraction. It now offers a more flexible approach than many other law firms, and this is having an impact on its reputation as a great employer. As one recent joiner comments: “The flexibility offered was a huge factor in my decision to join Michelmores. My previous firm wanted fixed three days in the office, and my commute is long.”

It has also created the opportunity to attract candidates from a wider geographical area than before. Another new joiner says: “…being sure agile worked in practice was my first question. It meant I could join and not have to relocate.”

Michelmores continues to monitor and evolve its agile working approach, including understanding the impact on new joiners such as these and developing induction and onboarding processes to suit new ways of working. Valuing the different office sites and bringing people together in person continue to be important for the organisation as it grows. Working in an agile way encourages teams to use office time more intentionally and the Michelmores agile working approach, with the flexibility that it brings, is now firmly part of the organisational culture.

Colette Stevens, HR Director of Michelmores, summarises: “Timewise really listened to what we were grappling with and what was important for us. They helped us co-curate our approach to agile working and differentiate what we can offer the market.”

Published January 2024

By Amy Butterworth, Head of Consultancy, Timewise

It’s no secret that retail is a tough nut to crack when it comes to flexible working. The industry is the UK’s largest private sector employer, with around 5 million people in its workforce. But while some roles, such as sales assistants and head office staff, tend to allow for some part-time and flexible working, there’s a real lack of these opportunities within retail management. And that, in turn, is having a knock-on effect on companies’ ability to attract and keep staff.

So it’s pretty big news that Wickes, the home improvement retailer, is committing to making all roles open to flexible working, from the point of hire. What’s driving this decision? And how can they be so sure that it’s the right one? The answer – because they are passionate about creating a workplace culture where all colleagues can feel at home and thrive and because they’ve worked with us to explore the art of the possible and test it out.

While Wickes have had real success in making entry-level in-store roles more flexible, they had become aware that access to flexible management roles was very limited, and that their managers were finding it challenging to fit their responsibilities into their allocated hours. So before approaching us for support, they did some digging to try and find out why.

The process saw them interrogate the responsibilities of three management roles: store managers, operations managers and duty managers. This revealed occasional confusion about who should be doing what, which in turn was limiting the managers’ efficiency and effectiveness. It also highlighted that some managers felt a responsibility to be in-store that didn’t necessarily match service needs.

Mark Reynolds is Store Manager of Wickes in Tottenham. He says:

“Before the trial I was probably doing five long days in store. I remember having my review. I’d just won Store Manger of the Year. But my home life wasn’t great. My daughter was 3.5 and my other was newborn.”

“I’m a self-confessed workaholic, and put in all the hours I can. But I had started to realise that a change was needed. I wasn’t getting any time at home with my wife. She was getting no support from me. And I had started to drift from my friends, who always get together at weekends (when I used always to be working).”

Tanya Tozer works in the Worksop store. She has 3 children – all girls, aged 5, 9 and 12. Her middle daughter, Ava-May, has a rare genetic condition called De Grouchy syndrome which requires a lot of support at home. She says: “I didn’t think I needed to change my working pattern, but on reflection, I needed the respite more than I let on, more probably than even I realised I needed it. I had been struggling with my mental health.”

So, building on our many years of experience, we worked with the Wickes team to design, trial and evaluate a six-month pilot across 14 Wickes stores. This saw us supporting the managers to redesign their working patterns, with some opting to work four longer days in-store, and others flexing their hours across the week in a way that suited their lives.

They also kept a reflective diary to track their working hours, and identify why they might be working more than they should. And they were supported by us, and each other, with monthly feedback and learning calls.

As always with our pilots, we put in place a robust system of tracking and evaluation so we could really understand what worked and why. From this, we gained some valuable learnings, including:

The pilot also busted the long-held myth that managers need to be on-site at all hours, and highlighted the fact that when managers step back, they create space for their junior colleagues to step up.

There was no negative impact on store performance or KPIs, and the feedback we received from the pilot participants speaks for itself; 96.5% of store managers were either ‘satisfied’ or ‘very satisfied’ with their work-life balance at the end of the pilot (up from 66.5% pre-pilot).

But perhaps the best way to demonstrate the impact of the pilot is to hear from the people involved.

Tanya says the change to her working pattern, has changed her life: “Now, I can go to the gym, I can do some crafting. I have always had Tuesdays off, as these tend to be hospital days. But having Fridays off is really making a difference in my life. The girls are in school. It is my day for me.”

And it has also helped her team: “I think it’s had a really positive impact on the team. It has helped everyone feel more accountable. I’ve had to strengthen some of my weaker areas; build in more planning and more structure. I’ve also had to delegate more and it has been great to see the team step up to the challenge and grow.”

And here’s Mark again, on how this different way of working has affected him personally:

“At first, I felt a lot of guilt and responsibility. But gradually I realised – it was just about setting a new norm. Getting the processes in place was not easy, but once you get there – it’s a different way to live and work. A better one. I’ve developed a new phrase: happy home life, happy work life. I am a happier me.”

He’s also clear about the effect he believes it will have on the future of Wickes, and the retail industry as a whole:

“We have a WhatsApp group called Trailblazers – we all believe we are part of shaping the next generation. We feel part of something special. At the moment I am looking at ways to retain colleagues who are mothers, and possibly help them onto the management track. Make one small change and a thousand more will follow… people will stay and build their careers as their lives change. I don’t see any negatives whatsoever.”

Unsurprisingly, given the pilot’s success, Wickes are now rolling it out across all stores to more roles, those of duty manager and operations manager. They’re doing so as part of our wider Flexible Working for All action research programme, supported by Impact on Urban Health, with Guys’ and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust and Sir Robert McAlpine also taking part, which aims to show the impact of embedding good quality flexible working for all on both employees and organisations.

And as Louise Tait, Wickes’ Head of HR, OD and Talent noted when she appeared as a panellist at a Timewise webinar, there’s a hope within Wickes that the retail industry will have a mindset shift and start asking “What’s the right thing to do” when it comes to offering flexible working. With this kind of evidence of the power of flex to change companies’ cultures and people’s lives, why wouldn’t they?

Published January 2024

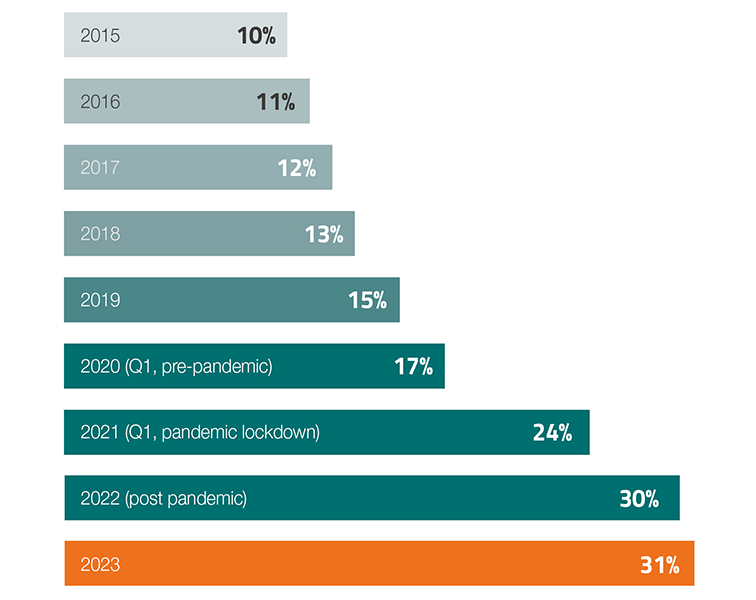

Our 9th annual Flexible Jobs Index© reports negligible change on the previous year’s level of job adverts offering flexible working. Only 31% do so, signifying an end to the progress that was made during and since the pandemic, when hybrid working became the norm for many UK jobs.

The stagnation is surprising in the light of the Employment Relations (Flexible Working) Act 2023, with its accompanying regulation giving people the right to request flexible working from day one in a new job. It suggests that many employers remain resistant to flexibility for new recruits, and are not preparing for the change that is coming when the new law is implemented next year.

To be fair to employers, complex workplace transformation takes time. And the pressure to adapt to flex coincides with huge challenges in terms of pay rises to cover the increased cost of living, whilst grappling with an economic downturn. However, it has never been more important to look beyond the barriers and consider the evidence that flexible working is a powerful talent attraction tool. Candidates increasingly want and expect to be able to work flexibly, and with new legislation on the way that is not about to change.

The proportion of job adverts which offer flexible working appears to be stalling. The 2023 rate of 31% represents barely any increase on 30% in 2022, and follows three years of a marked upward trend during and since the pandemic, as many organisations embraced hybrid-working.

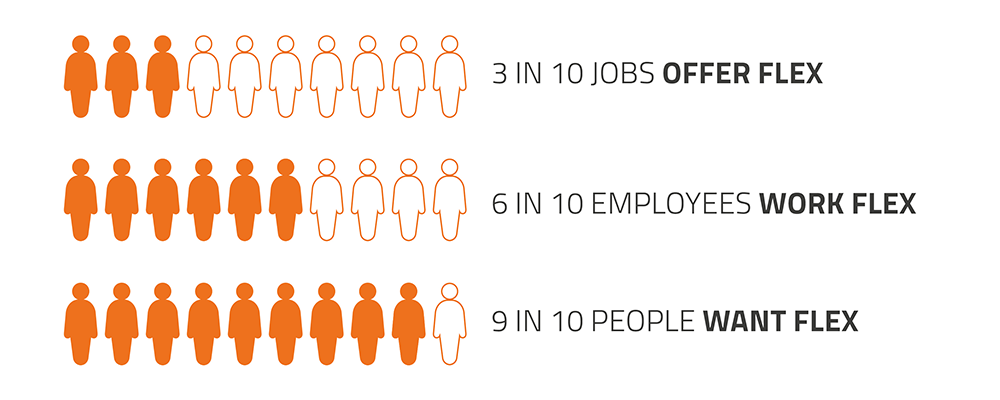

The supply of flexible vacancies lags far behind demand. 6 in 10 employees can access the benefits of flexibility in their current job, and many more people want to work flexibly. Yet only 3 in 10 jobs are advertised with flexible working – or, to look at it another way, people who need flexibility are unable to apply for 7 in 10 jobs.

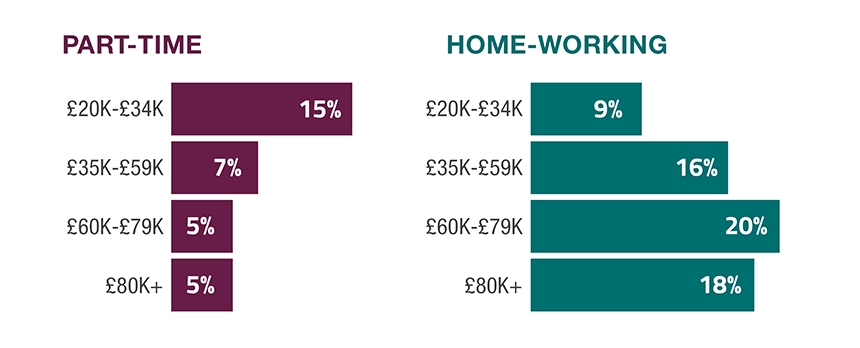

The higher the salary, the lower the availability of part-time jobs. Conversely, home-working (including hybrid working) is least available in lower paid jobs and peaks for jobs paid £60k-£79k.

These imbalances create unfairness in the workplace. The lack of part-time jobs at higher salaries traps many people in their low-paid part-time roles. It also creates barriers for those who take a temporary break from work and need a part-time role to re-enter the workforce. Meanwhile, hybrid arrangements, which make up the majority of home-working jobs, are primarily associated with higher-paid office roles and are inaccessible to many.

Greater parity can be achieved, if employers look more closely at what flexibility is possible in a role and design it into jobs.

Access to flexible working at the point of hire varies widely depending on the type of role. Those that are largely based around shifts offer flex the most – for example social services (45% of job adverts) and medical/health (38%). Above average access to flex is also offered in a number of office-based role categories, because of increased home-working – for example, HR (39%), marketing (38%), and finance (38%).

But some role categories have stubbornly low rates of flex, such as manufacturing (11%), and construction (10%). This may be gender based – they are male dominated roles where historically low requests for flexibility may have shaped cultural resistance to it.

CIPD research published in May 2023 found that 49% of employers were not even aware of the 2023 legislation on flexible working, and the regulation around the day-one right to request it. So first, employers need to read up on the new legislation and think through how they will incorporate it into their processes.

The best way to gain knowledge and confidence on how to make flexibility work in your organisation is to find successful examples in your sector. Guidance on flexible job design will be helpful, as will advice on how to support line managers to implement flex.

Look particularly at how to make a success of hybrid working, which is currently the subject of much doubt amongst employers. Before you row back on hybrid, or decide not to trial it, invest time in understanding models that are successful.

And finally, it’s a mistake to assume that candidates will know they can ask for flexible working at interview. People who need flex want to know it’s on offer before they waste time on an application. This is especially true if they have been out of the labour market for a while, as they may lack the confidence to ask. So be sure to state clearly in your job adverts which types of flexibility are possible for the role.

Watch the Timewise Flexible Jobs Index© 2023 webinar below:

New legislation, which includes the right to ask for flexible working from day one in a new job (informally known as Day One Flex), is likely to come into play in early 2024. And while common sense suggests that this will be a popular change, and we and other campaigners have long believed that it’s necessary, there’s not really been the data to back this up – until now. As part of a substantial new programme of research to better understand workers’ attitudes towards part-time, we have partnered with Opinium to survey 4,000 workers. And among the questions around access to flexible working in general, we asked if they knew about the new legislation and if they’d take advantage of it – whether in a new role or in their current one.

Half of respondents would consider asking for flex from day one When asked whether they would consider taking advantage of the new Day One Flex rights in a new role, almost half of our 4,000 respondents (49%) said yes. Additionally, 30% said they weren’t sure – which may partly be because over two-thirds of respondents weren’t aware of the change in the rules before taking our survey. And only 21% said no.

The research also dug into the detail of who would be most likely to consider using the new rights, and this threw up some significant variations, with three determining factors emerging:

The government has confirmed that the right to request flexible working should be a day-one right for all employees. The legislation also:

Interestingly, and unusually for the flexible working arena, one area in which there isn’t a sizeable discrepancy is gender, with 51% of women answering yes compared to 48% of men.

We’re undertaking further research to deepen our understanding of the variations among different groups, and will be exploring the intersection of a number of factors, especially ethnicity, age, class and caring responsibilities. We’ll be launching our report in the autumn.

Remember – this isn’t just about new hires

While this part of the legislation focuses on the right to request being available from the first day in a new job, it’s important to remember that it won’t just affect new recruits. Currently, the right to ask only kicks in at 26 weeks, so the change would directly affect anyone who has joined more recently than that.

And while respondents were more likely to use the new rights in a new role than in a current one, our findings also show a strong interest in using them to change existing working arrangements, especially among those who are less comfortable having informal conversations about flexibility with their manager. 40% of all workers said they would consider using the new rights in an existing role, in comparison to 29% who wouldn’t. And again, this figure rises among workers who are from a black ethnic background, young (aged 18-34) or have caring responsibilities.

It’s also worth noting that, despite all the talk about the pandemic driving a shift in flexible working, our research shows that this hasn’t been the case for the majority of workers – especially those in routine occupations. 41% of workers in managerial and professional occupations gained flexible working during the crisis and say they have maintained those arrangements, whereas only 9% of those in routine occupations said the same. So in many organisations, there is likely to be a pool of employees who will want to take advantage of the new right to request.

What does this mean for employers?

So if this is what the data is telling us, what should you do about it? It’s simple really; you need to be prepared to manage an increase in flexible working requests, and to respond to them fairly and consistently.

This means building capability within your organisation on the different types of flexibility that are available, and evaluating how they could be incorporated into different roles. It means equipping your line managers to respond to requests in a constructive way, which balances the needs of the individual with those of their team and your organisation.

It also means taking a proactive approach to ensure that open and transparent conversations about flexible working are possible for all workers, regardless of their role, and that the onus isn’t on the individual to have the confidence to request, whether formally or informally. We’ve explored seven ways that employers can get ready for Day One Flex here.

But as well as creating requirements for employers, the new legislation also creates opportunities. Yes, you need to comply with the legislation – but a much more powerful option would be to embrace it fully, and shift to a proactive approach.

One example would be to offer flexible working for all new candidates, and say so openly in your job adverts. As our previous research has shown, doing so is likely to widen the pool of candidates both numerically and from a diversity perspective, which would in turn have a positive impact on your organisational culture and employer brand. Of course, this will need to be backed up by flexible options for existing staff too.

So are you ready? The data says you need to be, and the clock is ticking; it’s time to get started. If you’re not sure how, we can help; feel free to get in touch.

Published June 2023