We brought employers from different sectors together to discuss how to support more young people into secure work with greater choice, autonomy and control.

By Tess Lanning, Director of Programmes

The next 12-18 months present a critical opportunity to improve employment outcomes for young people, as the government introduces a range of initiatives to tackle a rise in worklessness and insecurity.

As well as an increase in the age young people will be able to claim health-related benefits, this includes initiatives to improve the quality of jobs available. A new Youth Guarantee commits to providing decent training, apprenticeship and job opportunities for 18 to 21 year olds, while the Employment Rights Bill seeks to tackle high levels of low pay and insecurity in the economy.

Job insecurity disproportionately affects young people. Government statistics show that one in eight young workers are on a zero-hour contract, compared to less than one in 40 older workers, and young people are more likely to work volatile and variable work schedule patterns. Research has shown this is not only bad for early career job prospects – but can have a lifelong negative impact on employment, earnings and health outcomes (see Paul Gregg’s 2024 thought paper on future policy and Wen-Gui Han’s research article in to the effects of employment patterns on health in the US).

Government action to tackle these issues is therefore to be welcomed. But will employers engage with these initiatives? And if so, will young people see the benefits?

In June 2025, Timewise and Youth Futures Foundation gathered with employers from diverse sectors to find out.

Employers highlighted the focus on securing employees that can ‘hit the ground running’ in the context of rising financial pressures, combined with a reliance on tried-and-tested recruitment, selection and induction methods that favour older and more experienced workers.

Critically, they felt that there was a mismatch between dominant workplace cultures and the values, needs and expectations of younger workers – particularly in frontline sectors, where employers were finding it difficult to provide greater stability, security and flexibility at work. Many were struggling with skills gaps and vacancies as a result.

Employers had ideas for how to tackle these issues – from changes to hiring practices, management training, and more visible information about pay, progression and flexible working policies, to the creation of employee forums to co-design and support changes that improve long-term employment and health prospects for young people.

But they also highlighted the need for more support and evidence to inform good practice – particularly on issues affecting job security, such as scheduling practices and shift patterns. Without this, the new legislation may fail to hit the mark for young people.

Get in touch to understand how you can implement or inform good practice in these areas: info@timewise.co.uk

Published July 2025

By Nicola Pease, Principal Consultant, Timewise

We can all agree that any functioning society needs an excellent system of early years and childcare provision. At present, our high quality early years educators are managing to provide a great service, but many are stressed, exhausted and have little to no work-life balance. In short, it’s an early years system on the edge.

While issues around pay and progression loom large with no immediate resolution in sight, let’s look to what we can fix. Building on recent successes in other shift-based, site-based sectors such as nursing, construction and retail, Timewise launched a report following an in-depth two-year project in the early years and childcare sector. Thanks to support from JPMorganChase we were able to partner with two leading childcare providers: the Early Years Alliance and the London Early Years Foundation, and get close to childcare staff, in settings.

We analysed the industry’s challenges and assessed its potential with regards to improving staff wellbeing through changes to working patterns. Sometimes, even the smallest changes can make an enormous difference. We conducted all our research and analysis whilst keeping the experiences of children and parents front of mind. If this is going to work: it has to work for everyone.

We held a packed event in Westminster, with support from the Early Education and Childcare Coalition, to launch our subsequent report, Building the early years and childcare workforce of the future, with early years providers, policymakers and local and national government representatives. We collaborated on ideas and sharing ‘what works’ at settings across the UK. All with the experience of children and quality of education and care, front and centre of our thinking. Read on, to find out more…

The early years sector is facing a perfect storm – the expansion of 30 hours funded childcare will require an additional 35,000 staff across the UK, yet 78% of providers in a recent survey said they are already struggling to attract people to a sector that is not competitive on pay or working conditions. 62% of the workforce earn less than the living wage, with pay rates similar to roles in retail and hospitality, that are arguably less physically and emotionally demanding – and sometimes offer more flexibility in terms of what shifts and hours people can work.

There is also an increasing number of pressures on our early years educators which is driving up their workload and making the job harder. For example a growth in the demand for longer-hours provision to meet the needs of parents and (as was raised numerous times at our event), a hugely increased number of children presenting with SEND. All this notches up the pressure gauge.

The research found that nearly two-thirds of staff in group-based settings have said they do not have good work-life balance.

Part-time work across the sector has fallen in the majority of settings since 2018-19 with flexible working options generally achieved through the use of casual, agency or bank staff.

Managers recognised the potential benefits of offering flexible working but were concerned about continuity of care, maintaining staff-child ratios, meeting training standards, ensuring fairness and managing team dynamics. As one person described life in a nursery, “It’s a constant jigsaw.”

At the roundtable we heard a clear call to value those working in Early Years more highly, recognising that, “It’s not just about numbers, it’s about ensuring those who care and educate are energised, valued and motivated to do so.” There was an acknowledgement that emotional resilience is key in a workplace that demands a high level of emotional investment in children’s development and needs. And a sense that there is a need to better balance the workloads and schedules of those in such an intense working environment, to better support physical, mental and emotional wellbeing.

Increasing access and opportunity for the sector is a challenge, but through the research and numerous examples of good practice, it was proven to be possible within the operating constraints of the sector – all with the voice of the child front and centre. Innovative work practices included split-shift patterns (read Ruth’s story on page 11 of the report) and recruiting lunchtime assistants (page 18 of the report), housekeepers or tea-time assistants who enable flexibility across the wider teams. As Neil Leitch, Chief Executive of the Early Years Alliance put it, “You have to be creative. Continuity is critical but that does not mean you need always to see the same person.”

And it can also be used to enhance an organisation’s management capabilities. As June O’Sullivan OBE, the Chief Executive of LEYF said, “We need to think creatively about flexibility, in its wider context. For example, think flexibly about how you think about succession planning. It can help planning the next steps for staff or an experienced manager phase their retirement slowly, while helping a new manager to build their skills and knowledge.”

At a national level, Timewise is calling for a workforce plan that includes flexible working as a key strategic pillar. We estimate that a recruitment drive based around part-time and flexible working could attract staff to fill the equivalent of 17,850 full-time vacancies. That’s half the 35,000 shortfall the UK currently faces, to meet the expansion of 30hrs/week funded support.

Locally, we need authorities to bring networks of childcare providers together to share learnings, consider challenges and how to overcome them by exploring innovative practices such as sharing of bank staff. There was real momentum at our event around this idea – clearly they have a real ‘binding’ role to play. And for childcare providers themselves, we need to see a shift away from an individualised request-response model of flexibility towards a more pro-active whole-setting approach that encourages creativity and innovation and enables staff input into working patterns. To support this, Timewise have created a series of toolkits and resources for managers, which can be found here.

There is no magic wand with which to fix the staff and people problems that the early years sector is facing. But creating good standards of flexible working, in an industry where 98% of employees are women, many of whom have their own caring responsibilities, is not just good business sense. It’s a way to improve wellbeing and the lives of those playing the vital role of nurturing our future generations.

Despite being a critically important sector for the UK’s economy and society, childcare providers are struggling to recruit and retain staff. Delivering good quality early childhood education and care is key to enabling parents to work and contribute to economic growth, yet staff are facing longer hours and lower pay than comparable occupations for what can be more emotionally and physically demanding work.

This is not sustainable and action must be taken to improve staff satisfaction and to make those working in early years education feel more valued and supported. The pressure on the sector will only increase further as the government rolls out the funded childcare entitlement expansion over the next year, forecasting that an additional 35,000 new places for zero to two-year olds will be needed by September 2025.

The Timewise Childcare Pioneers project explored how proactive flexible working cultures could improve staff wellbeing and engagement and attract a more diverse pool of candidates – such as older workers and those with caring and health responsibilities.

We worked with the Early Years Alliance, representing 14,00 members, and the London Early Years Foundation, representing 40 nurseries, to explore the role improved flexible working could play in tackling the current workforce crisis facing the sector, and to understand what improvements are possible without compromising the quality of education and care that meets the needs of parent and children.

Then we designed and delivered a set of activities and tools to support nurseries to be more consistent in their approach to flexible working, and to help them to consider and trial new approaches to increase the availability of quality flexible work.

Our thanks to JPMorganChase and Trust for London for supporting this project.

Our initial diagnostic work found that part-time and flexible working is relatively common in childcare provider settings, and steps had been taken by both nursery providers to improve the information and support available to nursery managers to help them respond to flexible working requests fairly and consistently. However, staff felt that these arrangements were sometimes rationed, and their requests were not always seen as significant. They also felt that many managers set shift patterns without their input, and organisational needs were considered above staff needs, leaving them feeling less valued and less able to balance work and life commitments.

Head office staff and nursery managers highlighted that flexible working could make it harder to meet statutory staff-child ratios, recommended training standards, parents’ needs for flexible care, and provide continuity of care for the children. Managers are under pressure to juggle all these factors when setting schedules and are concerned that having more part-time staff and enabling flexible working patterns for some individuals would negatively impact others’ workloads.

“It’s really difficult because everything that we do is planned around ratios. And if you’ve already got a certain number of children and you’ve hit your maximum number of children with the staff that you’ve got, being flexible isn’t always possible.”

Nursery manager

“Flexible work works better in some types of settings than others. It depends very much on types of funding and types of hours parents need… More affluent areas means less availability of the 15 hour entitlement for two-year-olds, with an increasing focus on parents working three long days a week and wanting Monday and Friday off. Staff say Tuesday to Thursday are very mixed days and then Friday is half empty and Monday mixed. This has particular implications [for nurseries] as often the parents who want this have babies, and baby care needs high ratios and consistent care. Nannies and grandparents are also in the mix in different proportions in different settings.”

Director, nursery group

We found that leaders, managers and staff in nursery settings were keen to make improvements to their flexible working offering to help retain and attract staff, provided operational challenges could be overcome. With limited capacity to pilot new approaches due to high workloads and staff shortages, our project focused on improving the confidence, skills and knowledge gaps of nursery managers with a set of resources and tools.

The project showed that it is possible to improve flexible working in the childcare sector, and that this can be one part of a solution to current workforce challenges. However, it also highlighted the need for practical support to help employers implement changes in a sector where funding constraints and acute staff shortages are limiting the capacity for innovation.

If flexible working is to be adopted more widely across the sector, it is clear that concerted action is needed at both local and national level.

How to attract and retain talent through enhanced flexibility for the workforce

Published November 2024

By Sarah Dauncey, Head of Partnerships and Practice

Is part-time the forgotten flex? It certainly appears so. While hybrid and home working have been at the forefront during and since the pandemic, there’s been little, if any, focus on part-time. This is despite the fact that almost a quarter of the workforce (8 million people) work reduced hours, and that many people, particularly parents, carers and those with health issues, can only work if they can find a part-time role.

Here at Timewise, we’ve been championing part-time for almost 20 years, including by proving that part-time doesn’t mean part-committed through our much-respected Power List. But our concern that the need for, and value of, part-time work were being ignored spurred us to find out what part-time work really looks like today – and what it ought to look like in the future.

Backed by the Phoenix Group, Lloyds Banking Group and Diageo, we’ve carried out a large-scale study, A Question of Time. This saw us survey 4,001 workers, and run four focus groups, so we could understand how part-time work is perceived and experienced across the labour market, and how those experiences and attitudes vary by gender, age, class, ethnicity and other demographic factors. We also included some analysis of the Labour Force Survey, the UK’s largest study on employment services.

What we learned from our new evidence is that the picture is highly complex, with big disparities between how different age groups, gender groups, ethnic groups, and income groups experience and perceive part-time. We’ve always argued that there is no one-size-fits-all solution for flexible working, and this study certainly confirms that approach. Here are some of our key findings – and why they point to ‘fluid flexibility’ as the best way forward for employers and employees alike.

These are just some of the issues highlighted in our research; you can find more data and insights in our report. But, of course, the next question has to be, what should be done about it? If we believe that part-time is a valid working arrangement (which we, and forward-looking employers and policymakers certainly do) then how can we ensure it’s more widely available and doesn’t hinder career progression?

The short answer is: we need a more fluid approach to flexibility. One that better supports employees to manage their work / life balance, while acknowledging that one-size-fits-all doesn’t even apply to one person throughout their career, let alone to a workplace as a whole.

After all, just because someone wants to work part-time when they have a young family, it doesn’t mean that they won’t be able to increase their capacity at a later date. And just because someone has worked full-time throughout their career, it doesn’t mean they might not prefer to work part-time to ease into their retirement. So, as one of our older research participants put it:

“There needs to be a flexible approach to flexibility – a rethinking of it so that working arrangements can be adjusted more easily. (…) Jobs need to be designed more flexibly and fluidly to respond to people’s needs and changing life circumstances.”

Employers who understand this will be better able to attract staff, and from a diverse range of backgrounds, retain them, and enable them to thrive. And they can make this possible by:

There are many more recommendations in our report, including some for policymakers, which we don’t have room to include here. But they all point to one thing: if we want to get part-time and flexible working right, the answer is fluid flexibility, which gives people more choice and control throughout their working lives.

Published December 2023

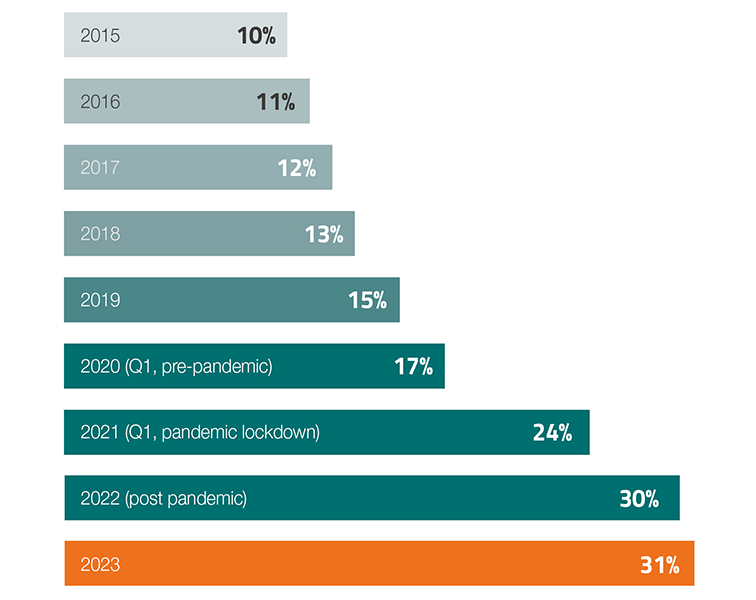

Our 9th annual Flexible Jobs Index© reports negligible change on the previous year’s level of job adverts offering flexible working. Only 31% do so, signifying an end to the progress that was made during and since the pandemic, when hybrid working became the norm for many UK jobs.

The stagnation is surprising in the light of the Employment Relations (Flexible Working) Act 2023, with its accompanying regulation giving people the right to request flexible working from day one in a new job. It suggests that many employers remain resistant to flexibility for new recruits, and are not preparing for the change that is coming when the new law is implemented next year.

To be fair to employers, complex workplace transformation takes time. And the pressure to adapt to flex coincides with huge challenges in terms of pay rises to cover the increased cost of living, whilst grappling with an economic downturn. However, it has never been more important to look beyond the barriers and consider the evidence that flexible working is a powerful talent attraction tool. Candidates increasingly want and expect to be able to work flexibly, and with new legislation on the way that is not about to change.

The proportion of job adverts which offer flexible working appears to be stalling. The 2023 rate of 31% represents barely any increase on 30% in 2022, and follows three years of a marked upward trend during and since the pandemic, as many organisations embraced hybrid-working.

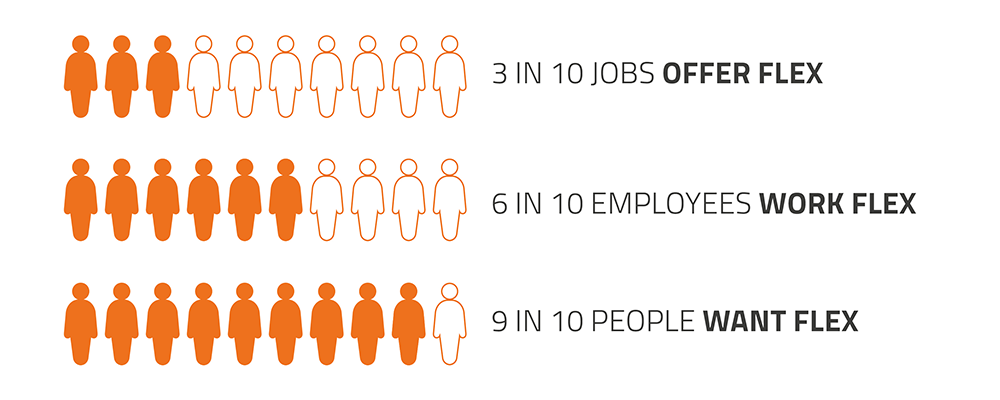

The supply of flexible vacancies lags far behind demand. 6 in 10 employees can access the benefits of flexibility in their current job, and many more people want to work flexibly. Yet only 3 in 10 jobs are advertised with flexible working – or, to look at it another way, people who need flexibility are unable to apply for 7 in 10 jobs.

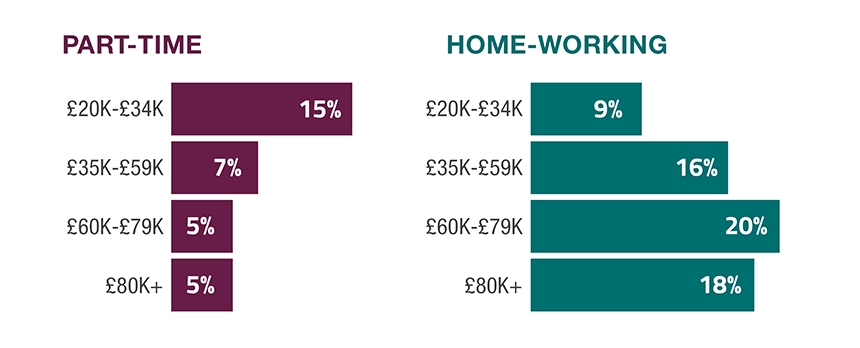

The higher the salary, the lower the availability of part-time jobs. Conversely, home-working (including hybrid working) is least available in lower paid jobs and peaks for jobs paid £60k-£79k.

These imbalances create unfairness in the workplace. The lack of part-time jobs at higher salaries traps many people in their low-paid part-time roles. It also creates barriers for those who take a temporary break from work and need a part-time role to re-enter the workforce. Meanwhile, hybrid arrangements, which make up the majority of home-working jobs, are primarily associated with higher-paid office roles and are inaccessible to many.

Greater parity can be achieved, if employers look more closely at what flexibility is possible in a role and design it into jobs.

Access to flexible working at the point of hire varies widely depending on the type of role. Those that are largely based around shifts offer flex the most – for example social services (45% of job adverts) and medical/health (38%). Above average access to flex is also offered in a number of office-based role categories, because of increased home-working – for example, HR (39%), marketing (38%), and finance (38%).

But some role categories have stubbornly low rates of flex, such as manufacturing (11%), and construction (10%). This may be gender based – they are male dominated roles where historically low requests for flexibility may have shaped cultural resistance to it.

CIPD research published in May 2023 found that 49% of employers were not even aware of the 2023 legislation on flexible working, and the regulation around the day-one right to request it. So first, employers need to read up on the new legislation and think through how they will incorporate it into their processes.

The best way to gain knowledge and confidence on how to make flexibility work in your organisation is to find successful examples in your sector. Guidance on flexible job design will be helpful, as will advice on how to support line managers to implement flex.

Look particularly at how to make a success of hybrid working, which is currently the subject of much doubt amongst employers. Before you row back on hybrid, or decide not to trial it, invest time in understanding models that are successful.

And finally, it’s a mistake to assume that candidates will know they can ask for flexible working at interview. People who need flex want to know it’s on offer before they waste time on an application. This is especially true if they have been out of the labour market for a while, as they may lack the confidence to ask. So be sure to state clearly in your job adverts which types of flexibility are possible for the role.

Watch the Timewise Flexible Jobs Index© 2023 webinar below:

By Melissa Buntine, Principal Consultant, Timewise

The launch of the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan is a hugely welcome development. The staffing crisis has been an ongoing issue within the service, with the RCN seeking legislation to protect safe staffing levels as far back as 2017. And in the intervening years, organisations within and outside the medical sphere – including Parliament’s cross-party Health and Social Care Committee – have warned that the number of unfilled posts (currently standing at 112,000) is a risk to patient safety.

The NHS took a big step towards tackling the problem with the publication of its People Plan 2020/21, which recognised the importance of flexible working as an attraction and retention tool, and committed to encouraging its employers to offer it from day one. And here at Timewise, we’ve also been focusing on this issue, working with 93 English NHS organisations last year on the Flex for the Future programme, to support the transition to more flexible working practices.

So we’re delighted that the Workforce Plan puts flexible working in the NHS at the heart of its measures, and recognises the impact it can have on staff shortages. But we also know that it will take a concerted effort to bring these commitments to life.

The plan’s commitment to “highlighting the flexibility and autonomy that NHS staff enjoy” is hugely positive, but making sure that this flexibility is fit for purpose is something else entirely. And while the People Plan’s day one flex commitment put the NHS ahead of the flexible working curve, the new legislation that makes this a UK-wide right softens that edge – and increases the likelihood of potential employees finding better-paid flexible opportunities elsewhere.

The NHS therefore needs to not just offer and highlight flexible working, but to champion it, from top to bottom, and make sure it works in practice. Here are four actions that the service could take to make this a reality.

1. Be more proactive about designing part-time and flexible roles

As in many organisations, there’s a tendency within the NHS to wait until people are about to leave, panic, then try to work out how to persuade them to stay. Flexible working is a brilliant retention tool – but instead of waiting until people have had enough, it makes more sense to offer it proactively, and to work with each individual to explore what kind of flexible working matches their needs.

We know from experience that there’s a real lack of confidence within the service about flexible job design, but it isn’t rocket science; at its core, it involves looking at when, where and how much people want or need to work, and designing the job to match. We can help.

2. Offer alternatives to the 12.5-hour shift norm

Again, as in many longstanding organisations, there’s a feeling across the NHS of “It’s always been done this way… if it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.” The length of a standard shift – a back-breaking 12.5 hours – is a perfect example of something that could merit a fresh look.

Leaders need to have the confidence to challenge this norm, and explore whether other alternatives could also work. Would it be possible to offer 6-hour shifts instead, which might be easier for people who are juggling family or caring responsibilities, or with health conditions? What would be the impact on staffing levels if they did?

3. Embrace self-rostering to give staff a say in when they work

The NHS has a high proportion of frontline staff, who work on a 24/7 shift pattern. Historically, these employees have had shifts imposed on them, and have needed to be available at any time, which is not helpful for anyone’s work-life balance. But thanks to developments in technology, it’s now possible to build rosters which take people’s preferences about when they do and don’t work into account.

We’ve previously piloted a team-based approach to rostering within nursing, using our ‘shift-life balance’ model, and found that it increased the feeling that work-life preferences were being met (from 39% to 51%), and improved the sense of a strong collective responsibility (from 16% to 36%). Both of which, clearly, are key to creating an environment in which people want to stay.

And right now, we’re working with several clients, including UCLH and Guys & St Thomas’, to introduce a self-rostering model. This allows team members to input their preferences into a roster, with ward managers then making final decisions to ensure safe staffing levels and the right skills mix. It’s a win-win, with staff really valuing the chance to have some input, and managers finding it can make the roster building and approval process much more efficient.

4. Make sure that all training can be done flexibly

The plan rightly places a big emphasis on training, both in terms of growing and upskilling the workforce. But in both cases, this training needs to be delivered in a way that is accessible to those who need to work flexibly. Otherwise, key groups who need flexibility to work – including, but not restricted to, parents, carers and those with health conditions – will fall behind their peers and potentially fall out of the workforce, or be prevented from joining it in the first place.

Clearly, changes like these take time to implement – and they won’t happen without board-level buy-in. So the NHS needs its leaders to step up now, and lead from the top, driving the behaviour change that the service needs, and even incorporating flexibility around ways of working as a design principle for their services. Professor Joe Harrison and his leadership team at Milton Keynes University Hospital are great examples of what can be achieved when leaders are vocal about the benefits of flexible working within the NHS.

It also needs to make sure that managers and HR teams have the skills they need to design and implement flexible roles. That means teaching them about the benefits of flexible working for the organisation and its staff; upskilling them in flexible job design; and training them in how to manage flexible teams. Our Flex for the Future programme set out how this can be done.

And finally, for all these recommendations to really take hold, they need to be applied across NHS systems, rather than on a trust-by-trust basis. We’re currently working with three systems –Lincolnshire, Kent & Medway, and Hampshire & the Isle of Wight – and are already seeing the value of bringing together the different parts of a local health and care system to collaborate on strategy, resources and learning. Implementing flexible working across the NHS in this way could be transformational.

And a transformational approach is what’s needed; as the Workforce Plan acknowledges, “Inaction in the face of demographic change is forecast to leave us with a shortfall of between 260,000 and 360,000 staff by 2036/37.” Patient safety is already at risk with today’s shortfall, and we can’t afford to let it get worse. The plan is an important step in the right direction; now let’s act on it.

Published October 2023

By Claire Campbell, Consultancy Director

There’s no question that the four-day week is a hot topic right now. Every time we host a webinar, or meet a client, it’s one of the first things we’re asked about – and apparently, many employees are asking about it too. And as an organisation focused on how flexibility can help people thrive in their work and home lives, we’re very much on board with the concept.

But it’s becoming clearer with every conversation that there is a lot of uncertainty around the four-day week; firstly, about what it actually looks like in practice, and secondly, about the best way to implement it. So we thought it would be helpful to share some of the questions that we’re being asked, and our suggestions for how to answer them.

One of the most common questions people have about the four-day week is what it actually is – and this is important, because it’s not what many people think. Specifically, it doesn’t mean employees just get a free day off each week with no impact on the other four days. The leaders of the 4 Day Week Global campaign have worked hard to clarify this, but the misconception remains.

So if it isn’t that, what is it?

At a basic level, it’s a pattern that expects employees to do 100% of their job, in 80% of the time, for 100% of their pay. How? Essentially, by being more efficient; by improving productivity in a way that allows them to achieve the same in less time. So it’s about reducing your hours, but not your outputs.

This is another big question – and the answer is, it depends on the organisation. If you are considering implementing the four-day week, you will need to work with your teams to explore how they can deliver the same levels of service or productivity more efficiently.

Examples that are often cited include reducing unnecessary meetings, automating certain processes and redesigning others to involve fewer people. There was also a suggestion from the UK pilot programme that some people picked up their working pace – 62% of employees who took part said it increased, with 36% saying it stayed the same. And a couple of the participant companies took strategic decisions to reduce overall workload – such as letting go of minor clients or cancelling a couple of non-core projects.

The key point is that there isn’t a one-size-fits all solution for this. Your teams will need to work collaboratively to identify where efficiencies can be made, and then design working arrangements that work within the new parameters.

That might mean everyone gets a full day off each week, or it might mean people working five shorter days, or even an annualised arrangement. The ideal scenario would be to offer your employees options on how they spread their 80% of hours across the week, so they can find a pattern that fits with the rest of their lives.

It’s much harder to see how the four-day week can be made to work through efficiencies within roles in which there is a really strong correlation between the hours worked and the service provided, such as patient-facing, customer-facing and contact centre roles. So organisations with these roles, who believe in the concept, may have to invest in making it happen, on the basis that this will have a positive impact over time.

That’s certainly the approach taken by Citizens Advice in Gateshead, who took part in the UK pilot. Their solution was to hire extra staff to cover the extra hours, in the hope that the investment will be offset by a reduction in recruitment, retention and sickness costs; at the time of writing, this is a work in progress.

There is also an argument that, for industries that rely on agency staff, hiring more permanent staff to allow everyone to work fewer hours for the same pay could be offset by the savings on both agency costs and sickness absence. One to watch is South Cambridgeshire District Council, who took part in the initial UK pilot, and is now trialling a four-day week for refuse loaders and drivers. This will cost £339,000 extra over two years in increased staff and new lorries, but the council believe savings will be made through using fewer agency workers, as well as rationalising bin routes to reduce wasted time.

Right now, the ‘payback’ data on frontline four-day weeks is limited, although our own research has highlighted a more general correlation between flexible working and people taking fewer sick days. But companies with some frontline staff will need to give some thought to how they make it work for their roles, to avoid exacerbating the gap between flex haves and have-nots.

This is another real challenge thrown up by the four-day week, and one which organisations with part-time employees are working to tackle. During a discussion about the pilot, South Cambridgeshire District Council’s Liz Watts noted that “In terms of part-time hours, this was the trickiest bit.”

One solution is to reduce the part-timers’ hours in line with the reduction for full-time staff, but it’s arguably a stretch for someone who is working less than a full week to compress their hours even further without affecting outputs. This is particularly true if their part-time job was never properly designed to match the decreased hours – we know anecdotally that many part-timers are already squeezing a full-time job into fewer days.

As with turning a five-day job into a four-day one, the answer lies in collaborative discussion and job design; exploring what efficiencies can be made and looking at how to make the role and its outputs achievable within the available time. It’s certainly not a good idea to expect the part-time or compressed hours employee to continue on the same hours for the same pay while everyone else around them is seeing their hours reduced.

The short answer to this is yes – and if it’s implemented well, it’s likely to help you keep the staff you have, too. Why wouldn’t it? But there are a couple of things to be aware of here.

Firstly, if you think that offering a four-day week will help you recruit great people, you’ll need to tell candidates about it; there’s anecdotal evidence of companies not wanting to promote this working pattern in case it attracts ‘the wrong kind of candidates’. This is based on an (outdated, in our view) assumption that only slackers want to work fewer hours, and it doesn’t really make sense; you certainly won’t be able to attract candidates through the four-day week if you keep it quiet.

And secondly, if you’re recruiting at a time when you’re piloting the four-day week, you’ll need to make that clear – otherwise, if you decide to revert to a more traditional working week, you’re highly likely to lose your new recruits.

This is a great question – and one we don’t feel qualified to answer, yet. The recency of the four-day week pilots, and the lack of large organisations taking part, mean that the data is in its infancy, and it’s just too early to call.

It’s certainly fair to say that there’s a risk of increases in individual productivity and retention reversing if people start to slip back into old habits. But it’s equally possible that the long-term health and wellbeing impact of working fewer days could lead to sustainable and quantifiable benefits for companies.

So we hope that the organisations which are piloting and implementing the four-day week have robust tracking in place, and are willing to share the outcomes, so we can all learn what the real impact of this new working pattern is.

Published June 2023

New legislation giving employees the right to request flexible working from the first day in a new job (informally known as Day One Flex) will be in place from next year. It is a sign of huge progress for those of us who have long championed flexible working, and is set to shake up HR practices across the jobs market.

However, it’s important to reflect that the legislation is in some ways just the start of the journey. The changes it ushers in will be made tangible by the way that employers respond. And it’s becoming clear from conversations we’re having that many employers – and particularly those with frontline employees – feel they will need more support to both implement these changes and access their potential benefits.

With this in mind, we hosted a Timewise expert panel discussion to explore the Day One Flex questions that many employers are currently asking. Our speakers were:

Over 200 people attended the webinar, and before we began we sense-checked their views by asking two questions:

The session began with an address from Minister Hollinrake. He began by saying his 30 years of experience as an employer before becoming an MP have led him to believe that having good relationships with employees, as well as open dialogue and a considerate approach to the rest of their lives, is good for workplaces and so for employers.

He also noted that flexible working is a high priority for people who are thinking of returning to the workforce, and that with 8.7 million people of working age currently economically inactive, and business representatives desperate for skills and labour, increasing access to flexible working is a key focus of his department.

As he clarified, the change is a right to request, not a right to insist; and it is important to consider the needs of businesses and customers as well as of individuals. But the expectation is that an extra 2.2 million people will be brought into the scope of the legislation, which is an extremely positive development in today’s tight labour market.

A key aim of the legislation is to promote conversations between employers and employees, and other changes being introduced at the same time will improve this process. For example, making the employer responsible for consulting on the request before rejecting it will create space for a conversation about alternatives to take place.

Similarly, allowing two requests in a year instead of one, reducing the timescale for employers to respond to the request from three to two months, and removing the requirement for employees to set out the potential impact of their request, should all make the process easier to navigate.

Employers do still have the right to refuse a Day One Flex request. But the legislation prioritises quality conversation and consideration and aims to make the process fairer and to support best practice.

Dr Anne Sammon, a partner at Pinsent Masons, has many years of experience working with employers on the existing legislation in this area. She explored what the changes will mean in practice, and what employers should be thinking about.

Moving the right to request from 26 weeks to the first day in a new job is good for employees for many reasons. For example, in practice, candidates who are currently working flexibly may feel nervous about having to wait for 26 weeks into a new job to find out whether they will get the flexibility they want or need, and worry that putting in a request may disadvantage them.

It also brings clarity to employers; for example, with regard to issues around indirect discrimination. For example, not considering a request for flexible working from a working mother could count as indirect discrimination; so this legislation, with its requirement that the request is considered, could avoid issues of that kind.

A big change for employers will be the reduction in the time they can take to consider a request. Employers will need to look at how long their current processes are taking, and see whether this may cause any issues once the period is shortened from three months to two. It is possible for both parties to agree to a longer consideration period, but employers must make sure they are not pressuring employees to agree to one.

It’s also worth remembering that the quality of the reason for refusing a request can make a real difference. If an employee feels that the rationale they are given is fair, they are less likely to appeal. So the hope is that the new legislation will encourage employers to explain carefully why the request doesn’t work for the business, and engage with the issues at the heart of the request. Clarity and transparency will be vital.

Finally, while the legislation allows for two requests in a year, employers should be aiming to have conversations that balance the employee’s needs with those of the business, so they can find a compromise that works for both and avoids repeated requests.

Louise Tait leads an HR team which has spent the last few years working out what flexible working means at Wickes, and how it can be adapted for frontline employees. She believes the changes in legislation are welcome, but noted that challenges remain in terms of how to enable line managers to have better, open and transparent conversations about flexible working outside of a formal process, and to work out how to provide flexible options for all workers, including those on the frontline.

The majority of Wickes’ 8000 employees are in operational warehouse roles or customer-facing ones. The labour market within retail is highly competitive, and this has been exacerbated by the pandemic, with many women and people aged over 50 leaving the sector. Additionally, while 40% of Wickes’ employees are women, and 40% work part-time, these numbers drop significantly as people move through the leadership layers. So flexible working is seen to be a key way to attract, retain and progress talent across the organisation.

Having successfully adopted flexible working for office workers, Wickes have been working with Timewise to explore how to implement it for store leadership teams, and are currently embarking on a new approach within distribution centres. These experiences have provided four key learnings:

Aside from the obvious and proven business case, the pilot has thrown up powerful stories from colleagues who took part about the benefits that being able to work flexibly have had on their personal lives.

You can read more about how Timewise is supporting Wickes on their journey here.

Zurich is known within the flexible sphere for taking a new approach to flexible hiring with transformative results. They support the new legislation around Day One Flex, but have already started having these conversations earlier in the hiring process. Steve Collinson, their UK Chief HR Officer, shared his experiences of increasing access to flexible working and hiring.

In 2017, the company was approached by the Behavioural Insights Team (BIT) via the Cabinet Office, to explore whether a lack of access to specific flexible options was holding women back in their careers and contributing to the gender pay gap. The work involved using nudge psychology to deploy interventions derived from data, and then track the impact of these over time.

Using their own data, and working with psychologists and statisticians, Zurich created a hypothesis that a lack of consistent, explicit access to part-time and job share opportunities meant that fewer women were applying for promotions, or to join the firm, than might otherwise be the case.

BIT responded by asking them to switch their default to advertising all roles (internal and external) on a part-time, job share or full-time with flexibility basis, with the theory being that this would widen the pool of applicants. And the results speak for themselves: since switching their default advertising position:

The changes meant that Zurich reached a talent pool that they hadn’t previously been able to appeal to; they also discovered that people were starting to apply to them because their approach to flexibility gave a positive insight into their culture. Additionally, their gender pay gap has been reduced by 10% and they were placed in Glassdoor’s top 50 places to work in the UK.

Steve concluded by sharing four things to think about:

We ended the session by asking attendees to reflect on what they’d heard and how it would affect their approach going forwards:

Our panel then answered the following questions raised during the session:

Are you able to give us any more detail on when the legislation is likely to take effect?

Minister Hollinrake replied that the legislation should take full effect in 2024. This takes into account the parliamentary process that it needs to go through to become law, and also gives businesses time to prepare.

When you talk about ‘Day One Flex’, what exactly does that mean?

In terms of an official definition, the Minister noted that his department is drafting guidance to set this out clearly, and will be able to share this in the weeks ahead. And Anne agreed that having a specific definition of what Day One Flex means will be absolutely critical.

What would you like to see this legislation deliver for businesses and employees across the UK?

Anne referenced the hope that it will provide employers with the opportunity to move beyond the Day One right and look at building conversations about flexible working into the recruitment process. This will in turn help employers market themselves as flexible and allow candidates to be open and transparent during the interviews.

Steve agreed, explaining that at Zurich managers are encouraged to have conversations about flexible working during the hiring process, so there are no surprises later on. He believes that the legislation will create an expectation that employers will have a more open mindset, and that when they are able to be explicit about being open to a conversation before an employee joins the company, it will benefit everyone.

Louise noted that Wickes’ line managers are also encouraged to have these conversations at the point of hire. She hopes that, going forward, employers will shift their mindset further than the remit of the legislation and instead ask ‘What’s the right thing to do’ in terms of having conversations as early as possible.

Minister Hollinrake concluded by noting that work has changed dramatically from the old 9-5 model, and that the culture of work needs to change accordingly. There is a lot of talent locked up in people who can’t follow a traditional working pattern, and employers should not lock them out of their workplaces.

All members of the panel agreed that this is the future of the world of work, and that we are all on the change journey together.

Next steps for employers

If this panel discussion has raised questions about how your organisation will implement the new legislation, or inspired you to start thinking about offering flexible working even before Day One, we can help. You can find out more about the support we can provide on our website, including a diagnostic review of your readiness for the legislation, training for your HR teams and line managers, and an introduction to our team at Timewise Jobs, who are experts on flexible hiring.

Watch the Timewise Day One Flex webinar below:

Published June 2023

By Amy Butterworth, Consultancy Director

I’m sure few would disagree that an excellent line manager can make all the difference to an employee’s career. Those who feel supported to do their best work are likely to thrive; those who feel undermined or neglected may struggle (or vote with their feet).

So it seems sensible that, when workplace norms fundamentally change, organisations would make sure their line managers are trained to adapt their practice accordingly. And yet, despite the widespread uptake of hybrid working both during and since the pandemic, this hasn’t been the case.

Research from University of Birmingham has found that only 43% of managers had received any training in how to manage hybrid teams. It’s highly likely that these managers will be struggling to successfully implement hybrid arrangements, particularly more informal ones which they need to design, agree and monitor themselves. And this lack of training could certainly be a factor in the finding that 47% of line managers are finding work more stressful than pre-pandemic.

Both we and the Chartered Management Institute (CMI) believe that hybrid working is a hugely valuable tool in the flexible working toolkit, with the potential to support key workplace issues such as talent attraction, retention, diversity and wellbeing. And we both know from experience that, when line managers are supportive of flexible working, and role model it themselves, it makes employees feel significantly more comfortable about requesting it.

So we’ve come together to turn the knowledge gap on its head, by creating a programme of hybrid training that will build managers’ skills and confidence. This will not only enable them to support their teams to work in a hybrid way, but also help them think about how they could work flexibly themselves, which will have an impact across their organisation.

The training will be delivered as a six-week programme, and will focus on three core areas which our hybrid research identified as particular concerns: the role of a manager of a hybrid team; ensuring fairness and inclusion, and enabling connection and cultural cohesion. We’ll provide workshops for each area, supported by group clinics that will give participants the chance to come together and reflect on their learnings and practice.

All the sessions will be run by our expert consultants and will be backed up with helpful resources, case studies, tools and templates from both Timewise and the CMI’s libraries, which participants can take back to their workplaces and put into action.

We’re really excited about this partnership, which brings together two social businesses with a shared determination to make the world of work better for everyone. And because we also share a belief in the value of research, we’re running the first one as a pilot, with robust evaluation in place, so we can assess its impact on managers’ knowledge and confidence before rolling it out more widely.

The first programme will start in the autumn, and we’ll share our learnings from it once it’s complete, with the aim of refining and scaling up the training so that more companies can benefit. We can’t wait to get started and will let you know how we get on – watch this space.

Please click here to register your interest directly with the CMI: https://www.managers.org.uk/campaigns/making-hybrid-work-for-you/

Updated June 2023

By Nicola Smith, Interim CEO, Timewise

It would be reasonable to think, in the current situation, that employers would use every trick in the book to encourage people into work. The economy is crying out for growth, with employers struggling to recruit the staff they need and large numbers of people remaining economically inactive (particularly older workers and those who are disabled or have long-term health conditions). And the cost of living has soared, with a fierce knock-on effect on household spending power.

Yet despite this perfect economic storm that we find ourselves in, it seems that Scottish employers aren’t yet fully using one of the most powerful talent attraction tools at their disposal: flexible working. Our new Scottish Flexible Jobs Index shows that the number of jobs advertised as flexible is still just 28%. This is a tiny, 1% increase on last year’s figure, and doesn’t come anywhere near the demand, with wider research studies indicating that 8 in 10 Scottish people want to work flexibly.

For Scottish people for whom flexible working is a preference, this is incredibly annoying; for those for whom flexible working is a necessity, it’s a nightmare. And for Scottish employers who are working out how to coax people into their organisations, it’s very much missing a trick.

The fact is, there are many, many people who would work if the flexibility they need was there. There’s been much talk at a UK-wide level about bringing older workers back into the workplace; in an article in the Financial Times, Kim Chaplain from Centre for Ageing Better noted that the single most important change employers can make to tempt the over-50s to return would be to be more flexible about working hours.

There are also many other people who can’t work unless they can find flexible arrangements that help them meet their caring responsibilities, or cope with health issues, or keep a lid on their childcare costs. The cost of living crisis means that many of these people are more desperate than ever to join the workforce, but without access to flexibility, they remain frozen out.

And it’s also worth remembering that flexibly advertised jobs don’t just help people get back into the workforce. They also help workers who currently have a flexible arrangement to progress their careers, and boost their household incomes, by taking the next step up the ladder elsewhere.

So by offering flexible working up front when advertising new roles , Scottish employers could massively widen the pool of talent that they have to choose from, and get themselves out of the recruitment hole that many find themselves in. And given that the UK Parliament is about to pass new legislation allowing employees to request flexible working from their first day in a new job, it makes sense for employers to get ahead of the curve by offering it proactively.

As well as digging deep into the data about flexibly advertised jobs – including breakdowns by salary, role type and region – our Scottish Flexible Jobs Index also sets out our recommendations for how Scottish employers and policymakers can use flexible hiring to tackle labour market shortages.

For employers, these include:

And for policymakers, they include:

We know that the Scottish Government already understand how important this is; in recent years they have supported a range of initiatives, including the Timewise Change Agent programme that ran from 2020 to 2022, helping raise employer awareness of the benefits of unlocking jobs to flexibility. But now, more than ever, we need all stakeholders to pull together to offer far more of the flexible jobs that really could transform the Scottish labour market, for everyone.

Published April 2023